We see what happens in the brain when procrastination. Understanding the neuroscience of procrastination, we can propose a strategy to overcome it. Procrastinating has an important cost for the person, a cost that sometimes we are not entirely aware of it. Most important when procrastination is added to being driven impulsively towards an immediate reward.

As on other occasions, NeuroQuotient® will help us understand the neuroscience of procrastination. How is this neurobehavior and what brain systems are involved in it.

In case we had any doubt about what procrastination is, let’s start by defining it. For this it’s enough with what the Wikipedia tells us:

Procrastination, …, delay or postponement is the habit of delaying action or activities or situations that need to be addressed, replacing them by irrelevant or pleasant situations.

Let’s start with some examples to help center the problem.

The tendency of each person to procrastinate is more or less high. However, very few are those who can say they have never procrastinated.

Let’s look at a couple of cases that we have encountered, which will help us to focus the problem.

Example 1. A client told us …

‘When I have to prepare a report with a deadline for delivery, I always wait for the last minute´

‘I know that the result, in terms of quality of the report, would be much better if I took it with some more time. In addition, I would avoid the mental wasting and the stress of having it continuously present.

‘But, I think waiting is not wasted time. I think that meanwhile my non-conscious mind is working. So, in the final moment, when I do it, the ideas are already worked’

And he added …

‘Although, really, I think I need the adrenaline shot to get going at the last moment.’

Example 2. A friend told us …

‘I tend to leave things for the last moment. For example, when I have to make a presentation or training. Sometimes, the time has come for the truth without having almost anything prepared.

‘But, I have the experience that I am able to improvise and in the end ideas come up fluently. I grow up in difficult situations. I probably need this pressure to work at full capacity. ‘

‘Yes, of course I would like to overcome it. But this is not the time. On another occasion, with more time and peace of mind, I will ask you for support’

In both cases they are intelligent people with great abilities. They move forward without problems, regarding the perception of others. At least they think so. We are not so sure that it is; Without procrastination, very likely, they would be more valued.

The recurring thinking in procrastination is: ‘I will do it later. Now I don’t feel like it. (I feel like doing something else)

The examples cited will help us understand what happens in the brain. To understand the neuroscience of procrastination. How is the neuro-limiting behavior (which does not give us good results).

On the one hand, there is always a mental process, a habit of thought (a belief) that aims to justify postponement. In this part the prefrontal cortex (the thinking brain) is involved.

In the extreme case of, say, ‘a super procrastinator’, the self-justifying internal dialogue of the postponement would be, more or less:

‘I will later’. “I don’t have enough information now.” ‘Later, I can concentrate better’, etc.

But in the ‘super procrastinator’ there is something more serious. For the ‘super procrastinator’ too many times ‘then’ never comes. This is because they add the habit of procrastinating (in doing the important things) with impulsive action (towards irrelevant things), seeking immediate reward. From impulse to impulse, the important thing is forgotten.

In the two previous examples, self-justifying beliefs can be, respectively:

‘I think my mind is working in a non-conscious way’

‘I think I have a great capacity for improvisation’

But, in all cases, the underlying thinking could be left in:

‘I will at another time. Now I don’t feel like it.

There is not enough motivation to do what is really important.

And, we do anything more irrelevant than if we feel like it. We feel enough motivation to do this irrelevant thing.

What happens in the limbic, emotional part of the brain?

Motivation. This is the key word that leads us to focus on the most relevant part of procrastinating neurobehavior. That part that takes place in the limbic, emotional, brain area.

Let’s remember first how animals are put into action.

They do it in two ways, and always with the goal of survival:

1. The via to increase pleasure. With the reward brain system that starts with sensory signals reminiscent of reward, pleasure. The dog smells a piece of meat and is motivated to eat it. The neurotransmitter dopamine is essential in the reward system.

2. The via to minimize pain. With the threat or fear system and then the stress system. To face or flee threats. In this threat system the amygdala is key; and in the case of stress, the neurotransmitter norepinephrine in the brain and the neurohormone adrenaline in the body. Adrenaline makes the heart beat faster, the muscles tense, the bronchial tubes dilate … and so the animal can fight or run away.

Motivation precedes action, although the process is very fast and we are not aware of it.

In the case of humans, the main difference is that these limbic systems get going not only with direct sensory perception; they also start following internal cues. Human brain doesn’t distinguish among what perceives directly from what imagine or remember. In this process the (prefrontal cortex) is key.

For humans, if we are not facing a physical threat, the most efficient process to take action consists of the following:

1. Approach motivation. Something like ‘this attracts me’ in a non-conscious way. The reward system is launched by releasing dopamine.

2. Action. We could say, ‘Fight, in a healthy way’. With focus to non-immediate results. Investing energy efficiently in action, without fear or stress.

In some cases, in procrastination, there is neither desire (approach motivation) nor energy (for action). It is not uncommon that, at times, it may be associated to depression.

But, let’s go back to the previous two examples. It is obvious that in both cases the approach motivation does not appear. They take action at the last moment as facing a threat. With fear, not with pleasure. Fighting or running away. Following the threat that ‘there is no choice,’ why it is not possible to wait any longer. With the adrenaline of stress that comes immediately behind fear.

The extreme case of the super procrastinator, it does start up with the reward system, but it does so in an impulsive way. With a ‘not consistent’ dopamine, resulting from the evocation of an immediate reward (see dopamine fasting). Somehow, this happens to a greater or lesser degree in all cases. Procrastinating implies not doing the important thing, but instead we do something that we want more. The greater or lesser degree will be determined by the impulsivity.

Where is the difference between procrastinating or not in terms of action?

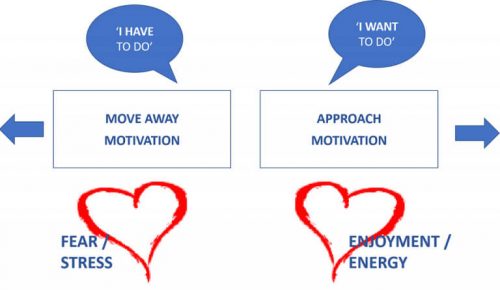

Figure 1 summarizes the neuroscience of procrastination attending how we move into action.

On the left we see what happens when we take action after having procrastinated. We act as a result of an obligation: ‘I have to do’, with threats / fear brain system and from stress. It is the move away motivation with which we want to avoid harm.

When we act directly, without procrastinating is in Fig. right side. In this case we do it from the will: ‘I want to do it’. Awakening the reward system, enjoying, and investing the energy necessary for the action itself, without excess epinephrine. It is the motivation of approach by which we start when something attracts us.

A new neurobehavior to overcome the problem

Given the neuroscience of procrastination, we can propose a solution to the problem. With what we have just seen it is quite simple, at least conceptually:

1. Identify those situations in which you have a tendency to procrastinate.

2. Do any of the cases involve an important limitation? First, it’s necessary to be aware that it is worth solving it. Going from ‘I have to fix it’ (at some moment that never comes) to ‘I want to fix it’ (already).

3. Schedule specific time (date and time) to do what you tend to postpone. It is not useful to write down only the delivery date.

4. Identify your limiting thinking. Your self-justification ‘jargon’ . That way you’ll know when you’re at risk.

5. Change to another habit of thinking, to replace the one that limits you. For example: When I have decided to do something, instead of connecting with ‘I will do it later’, move on to ‘it is worth doing it now’ or ‘I have a good time doing it’. It’s about not giving you the option to auto boycott.

6. Have an internal source of dopamine ready. Surely in your memory there are experiences that you do with great desire. In them is dopamine. Just train yourself to pay attention to one of them, so you can access your dose of dopamine when you need it to get going. You can create an anchor (see NLP anchors).

7. An added recommendation. If you have a high tendency to procrastinate, it is likely that you will also frequently take action impulsively, without thinking too much. Take advantage of it. Make a countdown from 3 to 0, and! Throw yourself! Don’t think on it!

Thus, in situations with a tendency to procrastinate, it is enough to focus the thought on the new belief (it will help to avoid the previous one), and pay attention to a memory that help your brain to release dopamine.

Design and practice a new neurobehavior that brings better results, greater satisfaction

In short, it is about designing a new neurobehavior. And, of course, put it into practice, to create brain connections according to the Hebb principle. The more difficult, of course, to overcome procrastination is to avoid procrastinating. If we postpone to fix the problem, we will never overcome it.

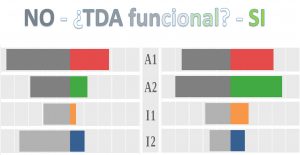

Finally, it’s important to remember that people with ADD (attention deficit disorder) have a high tendency to procrastination. It is logical, they tend to have an insufficient level of dopamine to start the approach motivation. In addition they have a greater tendency towards impulsivity. It is not weird to find many super procrastinators in this group of population.