We discuss on the relationship between memory and behavior. The NeuroQuotient® model helps us understand the most important elements and the structure of this relationship. From this, and from a personal experience, we point out possible impacts of the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic on the behavior of a baby, later on.

A question at the origin of this post

Our grandson was half year old the week of greatest impact of COVID-19. Will this episode influence his behavior and personality later? In which way could it happen?

This is how the idea to write this post came up. Of course, discussing about the relationship between memory and behavior is an opportunity to delve into the NeuroQuotient® model. However, we had not a way to go on with a specific the content.

Until an, in some way, similar episode of my life came to mind.

When I was exactly 6 months old (in February 1956) in Europe and especially in the Northwest Mediterranean, there was a wave of Siberian cold. Persistent “black frosts” killed evergreens, olive and carob trees. With low humidity in the environment, the low temperature freezes the sap of the trees. The economic and emotional impact on agriculture, and on my family, was very important.

Now, with a similar retrospective example, it is easier for us to point to the main relationships between memory and behavior. Also, it is easier to imagine how a certain experience can influence the behavior of a 6-month-old baby in the future.

(In addition, at the end of the article we will write down some curiosities about carob trees and their fruit: the E410 food additive, the origin of the word carat and something else).

How are we going to deal about the memory and behavior connection?

If we want to relate memory and behavior, we will have to start by being clear about what we mean by memory and behavior words.

To do this, at first, we will revisit some of the foundations of the NeuroQuotient® model on behavioral neuroscience. This will give us the opportunity to see and define different types of memory and their relationship to behavior.

From there we will be able to answer the initial question. For this we will point out possible influences of a specific and remarkable memory on behavior. Finally, we will illustrate these points with the referred personal experience.

Neuroscience of behavior with NeuroQuotient® … in animals

We will agree that animal species are, in some way, programmed to achieve their survival. In general, we could distinguish two types of behavior patterns that help this individual and collective survival:

- programs that promote behaviors that are rewarded with pleasure.

- programs or patterns that promote behaviors designed to minimize damage or pain.

These programs mainly ‘recorded’ in the brain and have neural foundation. For this reason, in the context of NeuroQuotient®, we speak of neuro behaviors.

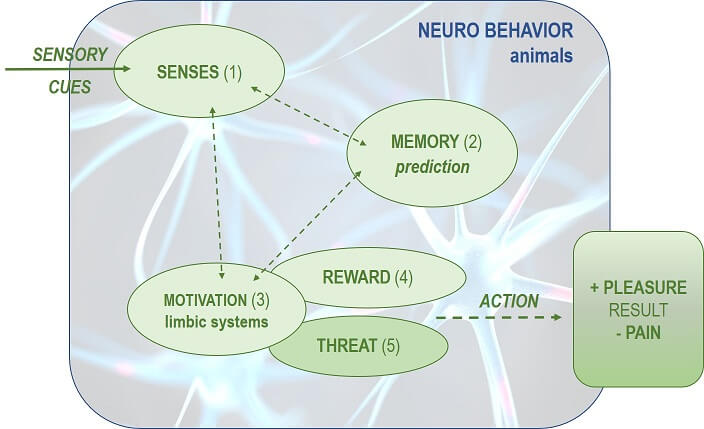

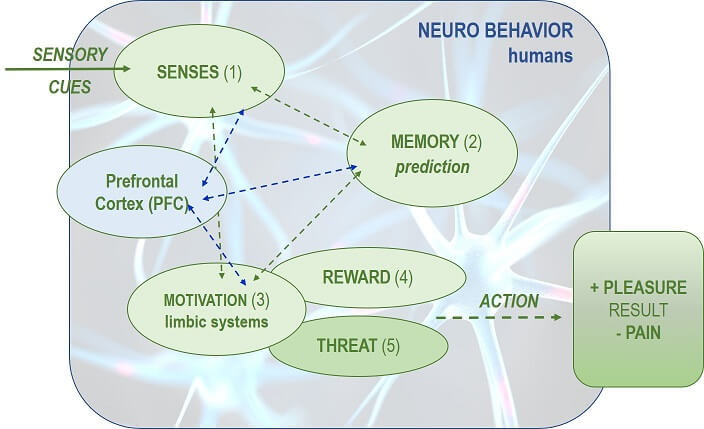

Let us now see (Fig. 1) the most important elements of these neuro behaviors.

The animal when explores its territory picks up cues with its senses (1). Sensory cues that may also come from within (feeling of hunger, for example). These signals are compared to memory (2), mainly that of the species.

Memory will predict behavior. According to the memory, the connection will continue towards one of the two most important limbic systems, which motivate (3) the action:

- The Reward System (4), which motivate action towards achieving pleasure. Promoting behaviors related to food and reproduction.

- The Threat System (5), which motivate actions aimed at avoiding harm. In this case they can be of three types. Fight, flight or freeze, depending on what the species memory indicates.

Although what has been said so far may indicate the opposite, neuro behaviors do not have a sequential pattern, but all connections are practically simultaneous. SENSORY CUE / MEMORY / MOTIVATION are connected as a set. It is very likely that a sensory stimulus activates all of the neuro behavior in a whole.

And in humans, how do these brain patterns or neuro behaviors work?

Humans have a part of the brain that distinguishes us from other mammals: the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the anterior part of the brain cortex (Fig 2.)

The prefrontal cortex gives us the ability to think and, at the level of neuro behavior, differentiates us by:

– Focusing the attention of our senses. When we explore the territory we do it much less randomly than the animals. The prefrontal cortex guides our attention.

– In addition, we not only explore outwards, but thanks to the PFC we also explore inwards. Our brain does not distinguish between what we directly perceive from what we imagine and / or remember.

Otherwise, our downward brain is practically no different from that of other mammals.

In other words, with the PFC’s conscious or unconscious approach, we can put in work the reward or threat limbic systems. All this with the intermediation of memory and with a greater part of memory learned than in the case of animals.

Let’s get more specific about memory and the relationship between memory and behavior

Let us remember that the initial objective was to deal about the relationship between memory and behavior. So far, when explaining important part of neuro behaviors, but we have been quite imprecise.

Let us now see different types of memory that have appeared to us and give them a small definition:

Species memory. The one that is engraved in the genes of the species. In the face of a free lion on the street, the natural human response will be to flee.

Memory learned, consciously. The experiences and learnings that we are able to remember. It has a very important role in the internal exploration of the PFC. Remembering, we can evoke sensory stimuli that trigger neuro behaviors.

Emotional learned memory (unconscious). By living an emotionally charged experience, a brain pattern can be generated. This pattern could determine our future behavior when faced with similar sensory stimuli. An extreme case is that of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Attention! Learned emotional memories can have a positive outcome. In a previous post we discussed on the anchors. With an anchor we seek to associate a sensory stimulus with an emotional response that empowers us.

Working memory. It is the information that we have at a certain moment in the conscious plane of our thought. Something like the RAM of computers. With it we bring the learned memories to the conscious plane.

Global memory. With global memory we want to refer, from NeuroQuotient®, to all the neuro behaviors of an individual. It encompasses the almost infinite set of brain networks. Some of these networks are activated depending on a stimulus, with more or less probability. We could call it almost quantum memory, because a sensory stimulus collapses the wave function like.

In the NeuroQuotient® context, neuro behaviors and global memory are the same

Neurobehaviors, patterns or programs are, therefore, neural pathways that in the face of a stimulus, generally sensory, from direct or evoked perception, guided by CPF (or not), trigger a certain type of behavior. In neuro behaviors, emotional memory plays an important role in motivation that drives action through reward and threats (or fear) limbic systems.

The brain connections underlying neurobehaviors are reinforced with use. Remember Hebb’s law: neurons that fire together wire together. This makes us behave, more and more, the same way in similar situations. The probability of a certain neurobehavior increases with the firing frequency of its underliying neuronal connection. In similar contexts, we think, act, move, etc., increasingly, in the same way.

Neurobehaviors refer to behavior broadly understood (perceptions, thoughts, emotions, actions, etc.) and the underlying brain connections.

Thus, from the NeuroQuotient® perspective, it is very difficult to distinguish between global memory and behavior because, basically, they are the same.

Possible influence of an experience at a few months of age in later behavior

We are now ready to answer the question we asked ourselves at the beginning. How could the memory of an event such as that of COVID-19 influence the behavior of a 6-month-old baby?

For this we are going to refer to the different types of memory that we have been seeing and, in some cases, we will illustrate it with the personal experience that we mentioned at the beginning.

At six months of age no learned memories are created that we can consciously remember in the future. So, we believe that the main memory and behavior connections, from greatest to least influence, could be related to:

- The event has a direct large emotional impact on the baby.

- Have an emotional impact on his/her closest family environment (parents).

- That in the future the event be remembered in the family environment.

- … and the tone and emotional intensity with which the memory arises in this environment.

- That in the future there are sensory stimuli that can trigger memory and associated neurobehavior.

Let’s look at it point by point …

1.The greatest influence would be with a direct emotional impact, that would create an ‘learned emotional memory (unconscious)’. If the baby would have COVID-19 (fortunately this is not the case) and he had to be admitted to a hospital. It is likely that later, with its exposure to a context with white coats, masks, the smell of disinfectant, a neuro behavior associated with the threat system (fear, with a flight or avoidance response, …) could be triggered.

2.Second level would be given by the emotional impact on the family environment. That his parents had a problem. Physical (suffering from the disease) or economic problems (with difficulty meeting basic needs), for instance. In this case, the impact of spending considerable time in a difficult emotional environment (including livelihood), could also be remarkable. It would not influence his/her conscious memories, but probably the creation of memory / limbic system connections (threats and or reward (food)).

3.Family memory. If the emotional impact on the family was significant, it is likely that the memory was recurred time by time in the family environment. In this case, the baby will not remember it on its own later on, but he/she could learn a ‘conscious memory’.

4.The emotional impact will depend on how the topic is dealt with, in the future, at the family level and on the emotional response that the boy/girl captures with his/her capacity for empathy.

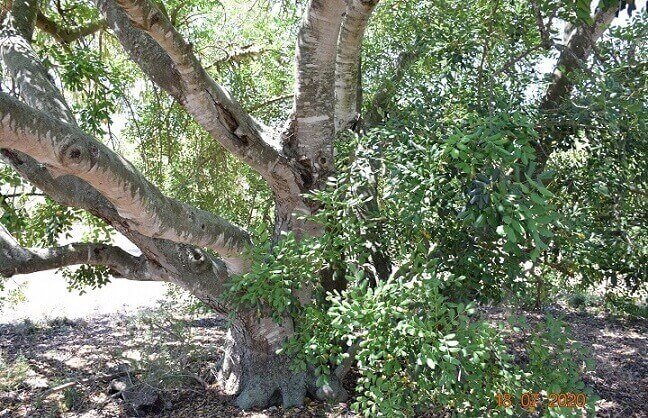

The trees (olive and carob trees) to which we referred at the beginning were ‘crowned’ (expression in Catalan that indicates a radical pruning).

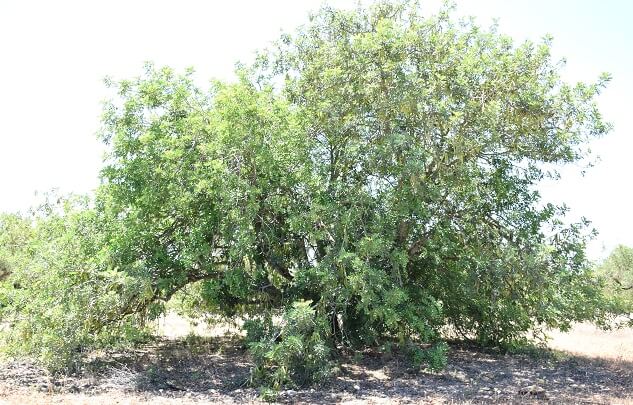

The olive trees were ‘crowned’ at the end of the larger branches and soon sprouted again (Image 1, one of the olive trees in 2020, 64 years after the frost).

The carob trees were cut by the trunk, just over half a meter from the ground. I remember the sadness that came to me from my parents and grandparents every time the topic came up.

Although the way of speaking was changing over the years. The carob trees also sprouted again, in this case from the root. 15 years later, with the new grafted buds, they became somewhat productive again. After the Covid-19 lockdown (the first?) We have been able to photograph one of them (Images 2 and 3 July 2020. 64 years after the frost).

Now (2020) they look like very big bushes more than trees.

Anyway, even now, when ‘black frosts’ (very low temperatures with low humidity) are threatening, my concern fires.

5.Finally, the presence of sensory cues that can activate memory and neuro behavior will also influence.

We said before, that at home from time to time the loss of the trees was present. At least once a year in the carob harvesting. I had not seen those old trees, but I could imagine them, because the dead ‘crowned’ trunks were there until the 1980s. Their vision acted as a sensory trigger for sadness.

Allow an anecdote to change emotionality. The trunks disappeared in the late 1980s. It coincided that a neighboring estate was parceled for weekend residences. Hence my father coined what he calls the ‘estate owner’ rule. It goes something like this: ‘The ‘estate owner’ puts a fence around his plot first, and tells: what is inside the fence is exclusively mine, what is outside belongs to everyone.’

Some curiosities about carob trees

We cannot finish without talking about the ‘points’ regarding the carob tree and its fruit that we referred to at the beginning of the article:

- The E410 food additive is ‘locust bean gum’ or ‘carob bean gum or carobin’. A natural food thickener that comes from the carob tree seed. It is used in juices, fresh cheeses, vegetable milks, in the kitchen, etc.

Therefore, not all E’s additives are synthetic chemicals. Or, perhaps, everything is chemistry or biochemistry in nature.

- The carob tree (ceratonia siliqua) in Italian is called ceratonia, in Latin ceratium, in Greek keration and quirat in Arabic. It is the origin of the word ‘carat’. In ancient times the carob tree seeds (which are very similar to each other) were used as a unit of measurement for metals and precious stones.

- The scientist Antoni Martí y Franquès (Altafulla 1750-Tarragona 1832) defended the theory of the sexuality of plants. At the end of the XVIII century he published ‘Experiments and observations on the sexes and fertilization of plants’. It included the carob tree. We can imagine that he had no doubts about the sexuality of the plants, when, walking through the fields near Tarragona, he noticed the smell of human semen given off by the male carob tree flowers in the fertilization period (late summer).