Behavioral neuroscience is understandable with the NeuroQuotient® model. In this post we explain for the first time the whole structure of the model. Its foundation is in how the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) connects with the limbic brain systems most relevant to behavior. These Systems are the Reward and the Threat Systems. With the NeuroQuotient® model we also see how neuro behaviors, brain patterns that include thought and emotion, influence the satisfaction of each person.

In almost every article on this blog we refer to the NeuroQuotient® model or tool. However, in none of them have we approached the structure of the model in a complete way.

In this post we will focus on the NeuroQuotient® model. The NeuroQuotient® model is a framework that explains the neuroscience of behavior in a simple way. The NeuroQuotient® tool is also based on this structure.

We will follow the script of the Introduction to NeuroQuotient® and Behavioral Neuroscience webinars which we have been conducting since 2016. We will start with an introduction to contextualize and then address the structure of the NeuroQuotient® model.

In a later post we will explain the process we have followed since 2007 (and more specifically since 2009), until the end of 2011 (moment of the insight about the model) and 2014 when we launched the tool and the first web application to manage it. In this other article we will also see how the dimensions of the NeuroQuotient® model are named, how they are related to each other and the meaning of the colors with which we represent them.

1. Introduction.

1.1. Where are our patterns of behavior?

Every day, for example, when we brush our teeth, we follow a certain pattern. That is, we do it in the same way. This is great because it is not necessary that we learn it again each time.

But we don’t just follow a pattern when doing physical activity. Let’s imagine that we are driving and that another driver crosses our path. When something like this happens to us, we may become scared and think something not very uplifting about the other driver. We may even get angry and yell at him. With this, we want to mean that when we talk about behaviors, within the NeuroQuotient® model, we are not referring only to ‘doing’ something, but we also include ‘thinking’ and ‘feeling’ (emotions and physical sensations).

And where are these complex behavior patterns that include thinking and feeling? The answer is that our behavior patterns are primarily in the brain. In part they are also in the body (physical sensations, muscular movements, breathing, etc.), although guided from the brain.

1.2 How are neuro behaviors generated?

If the behavior patterns are in the brain, then they must have a neural substrate, which is why we call them neuro behaviors. NeuroQuotient® deals with neuro behaviors, in short, the neuroscience of behavior.

To see how neuro-behaviors are generated, we can go to a previous post on the Hebb’s principle. Donald Hebb tells us that ‘neurons that fire together wire together’. For this reason, behavior patterns, neuro behaviors, become stronger the more we put them into practice.

It is great to have patterns that facilitate our behavior almost automatically. Above all, if we feel good about them, if they provide us good emotional results. But if the results are not good, if we do not feel good about the result of some of our complex behaviors, it is worth identifying and changing them.

1.3 Key elements in the NeuroQuotient® model

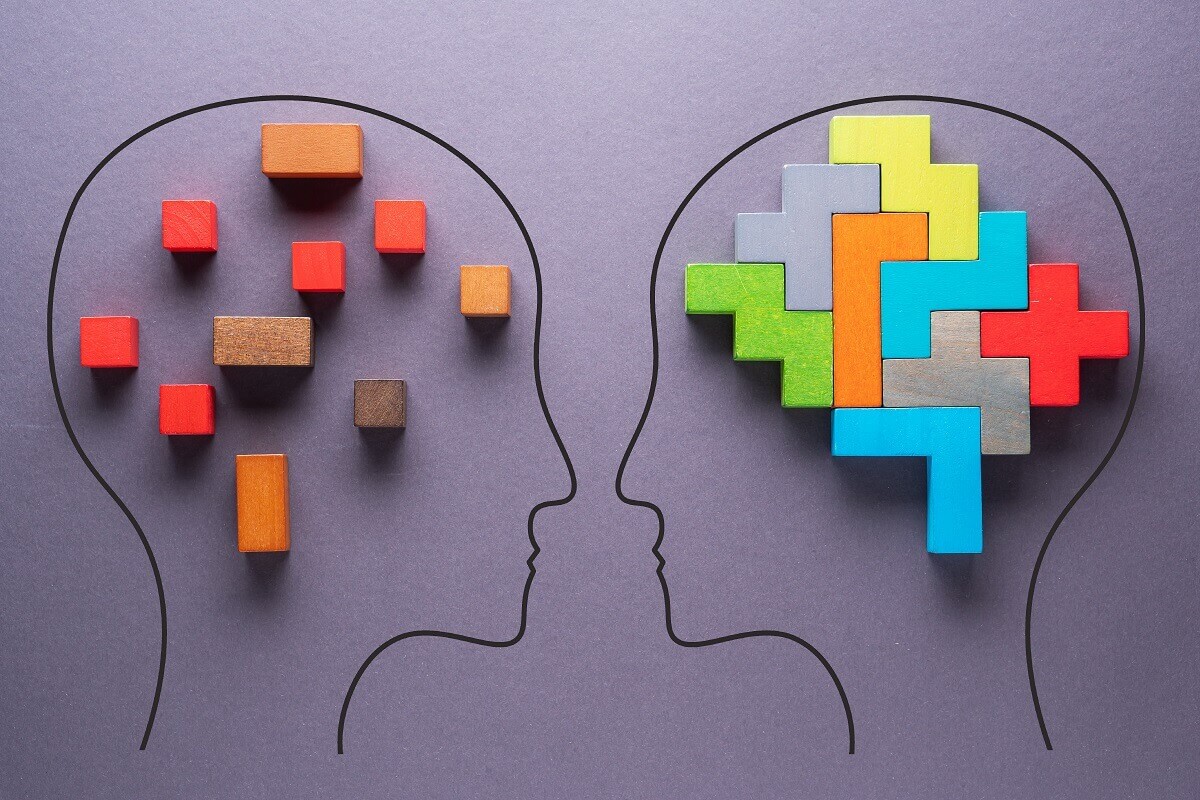

For this reason, in our model on the neuroscience of behavior, we distinguish between neuro behaviors that bring us satisfaction (why not happiness?) and others that impair our satisfaction. We call the former Efficiencies and the latter Limitations.

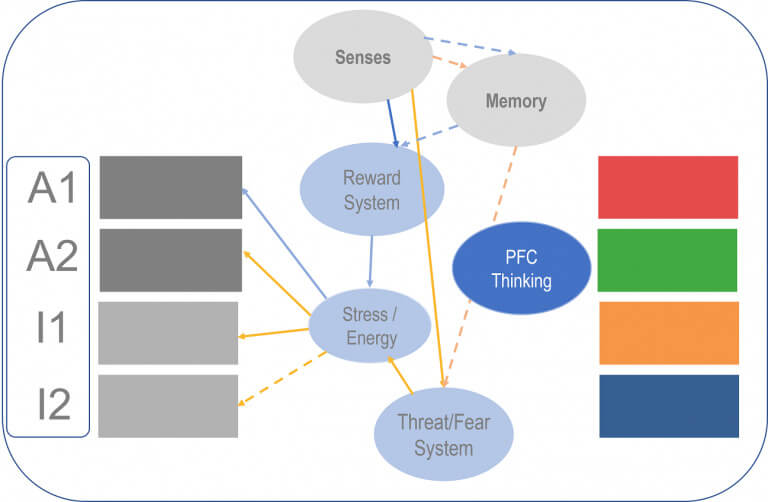

In Figure 1, we have an image (for a specific case) of the dimensions of the NeuroQuotient® model. Each dimension (A1, A2, I1, I2) groups neuro behaviors that, as we will see, have a coincident purpose. On the right side are the Efficiencies in color and on the left the Limitations in gray.

These Efficiencies and Limitations are like two sides of the same coin. When we have powerful efficient neuro behaviors, we can run the risk of limitations could be also high. We will see it later.

In the case of Figure 1 we see that, as often happens, initially could be some symmetry in the intensity of Efficiencies and Limitations.

Another key element is that we are facing a model on the neuroscience of behavior, not personality. In the NeuroQuotient® model we focus on behavior and its emotional outcomes. We are not dealing with personality. Personality, although it can evolve, is difficult to change. But, thanks to the plasticity of the brain, it is possible to adjust behavior to improve our satisfaction, well-being, and happiness. That is, increase the frequency of efficient neuro behaviors and decrease that of limiting ones.

Finally, with the NeuroQuotient® model, we simplify the neuroscience of behavior by identifying the brain subsystems that most influence neuro behaviors.

We had a hard time coming up with the NeuroQuotient® model, but, as we describe from now on, the structure is not complicated.

2. Neuro behaviors in animals.

2.1 The Reward System.

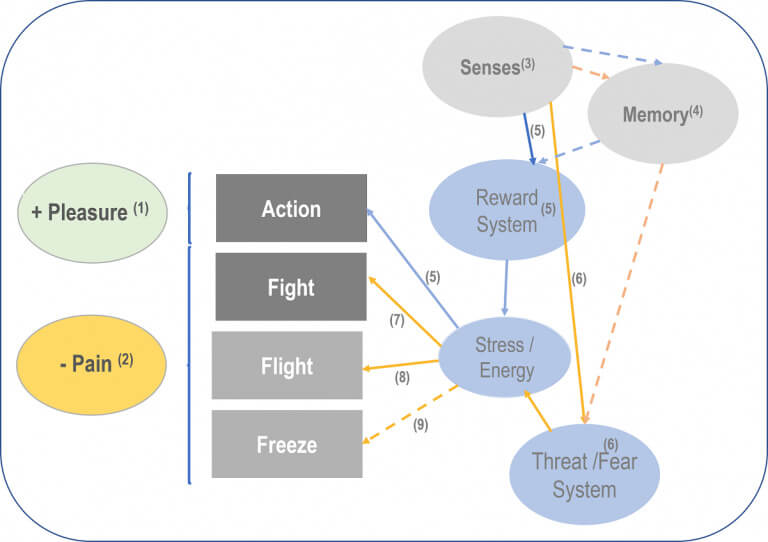

Let’s start by observing what happens with animals, the neuroscience of animal behavior. For this we will be guided by Figure 2.

Animal species, humans also, seek survival through two basic strategies: by seeking pleasure (1) and avoiding or limiting pain (2).

Animals get signals from the environment with their senses (3). These signals are compared in their brain to their species memory (4), and depending on what their memory indicates, animals will act one way or another.

Let’s imagine an animal perceiving a predictive reward cue (5).

What is a predictive reward signal? It is a signal which, its corresponding action, is rewarded with pleasure. There are two basic types: the ones related to feeding, and the ones related to reproduction.

Let’s suppose this: An animal (a dog) perceives (a bone) a predictive reward signal that starts up its reward system.

For example, a dog detects a bone (a predictive reward signal) that, through its memory, will activate its reward system (5). Consequently, the dog will eat the bone, and will most likely feel a sense of pleasure related to having eaten.

It’s important to clearly distinguish between the signal perceived by the brain, and its correspondent action and its results.

Let’s make a point. It is important to distinguish between the signal perceived by the brain, the motivation, the action, and its result.

Let’s imagine that the bone is poisoned. In this case, the signal will be the same, the Reward System will motivate the action, and the dog will eat the bone. But the result will not be exactly pleasant for the dog. We will come back to this example later.

2.2. The Threat (or Fear) System.

Let’s continue with Figure 2. But animals can also perceive other types of signals, such as threat or fear signals. Signals that threaten their survival. Then, in its brain, and through memory, the Threat Systems is activated (6). (In the case of humans, we will sometimes refer to it as the Fear System).

In front of these signals, animals have a range of options: If their memory indicates that this is a cue they can face, then the animal will ‘fight’ (7).

If memory indicates they can’t face the threat, that they are in serious danger, then they will flee (8).

But animals have a third option as well: Let’s imagine a rabbit feeding on grass across a field which perceives a hawk flying above it; a hawk searching/exploring for reward signals.

The rabbit will not attack the hawk or flee away, obviously. It will resort to a third option which is to stay still, to freeze (9), to become as little noticeable as possible in the eyes of its predator.

We have all seen a rabbit or a dog stand still in the headlights of a car. When the threat is very great, the animal gets stuck, ‘freezes’.

3. What happens with humans?

As human beings, we have something that sets us clearly apart from the rest of animals, which is our prefrontal cortex (PFC): the frontal area of our brain cortex. From the prefrontal cortex backwards and downwards, the human brain is not very different from that of, say, a rat.

The prefrontal cortex provides us, above all, two things. The first is that humans don’t explore territory as randomly as animals. The prefrontal cortex helps us prioritize and decide where we do want to focus our attention.

There is also another very important feature in humans: The human brain does not distinguish between what we perceive, what we imagine and what we remember. That means we can also initiate our neuro behaviors simply with our internal focus.

These two characteristics are fundamental in the NeuroQuotient® model to explain the neuroscience of behavior.

4. The NeuroQuotient® model. Neuro behaviors and emotional results.

In this section we will complete the NeuroQuotient® model on the neuroscience of behavior. For this we will see different possibilities of focusing attention, internally or externally, thanks to the prefrontal cortex, and its connection with the basic behaviors of animals.

We will also understand the neuro-behaviors of efficiency (that provide satisfaction) and those of limitation (not providing satisfaction) of which we spoke at the beginning. We will do it considering the emotional results derived from neuro behaviors.

Humans have obviously at least the same brain resources as animals. Our senses and our memory -in which there is a bigger part of learned memory- are similar. (in a previous article we discussed the relationship between behavior and memory). As well as our Reward, Threat or Fear, and Stress Systems.

But, as we said, what makes us clearly different is our prefrontal cortex (PFC), which enables us to focus our attention and thoughts. Next, we will see the different possibilities of this focus of PFC. In Figure 3 we have the set. We will advance dimension by dimension and build the NeuroQuotient® model to explain the neuroscience of behavior.

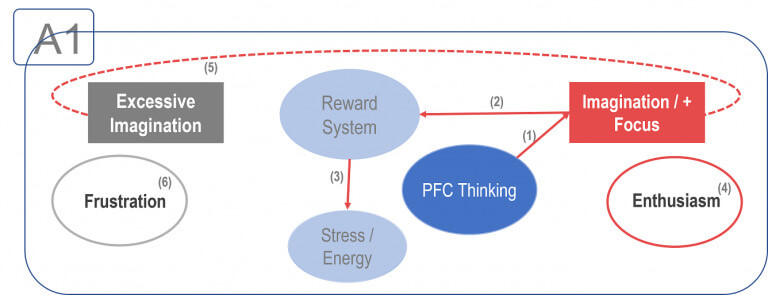

4.1. Dimension A1. Imagination and focus on positive and optimistic. The Reward System.

We can, on one side focus our attention (internally and externally) or imagination on the bright and optimistic side of situations and life (1). Follow it in Figure 4.

In this way, we can activate our Reward System (2), without needing a real signal from the outside, simply by focusing our internal attention.

Sometimes, acting will be needed as well (3). But the significant thing here is that we can activate our Reward System simply with our imagination, memory and/or attention.

In this way we activate the approach motivation. And when we do it in a habitual way, the emotional result we get is that we feel enthusiasm (4).

Without a doubt, this is an efficient neuro behavior. It gives us satisfaction.

However, as we said at the beginning, efficiencies and limitations are like two sides of the same coin. When we have an effective neuro behavior deeply ingrained, we run the risk of using it in a counterproductive way. Let’s remember the dog who was given a poisoned bone. It may be that the imagined sensory cue that motivates us and drives us to get going does not lead to a satisfying emotional outcome.

When our imagination is excessive or extreme (5), we may have many ideas and find it difficult to concentrate. Or that only with ideas we already feel rewarded and do not act. Even that we get carried away by the illusion that some unrealistic idea generates in us, and we act impulsively, following the spur of the moment.

In all these cases is difficult to get tangible results, and our ultimate result will usually be frustration (6).

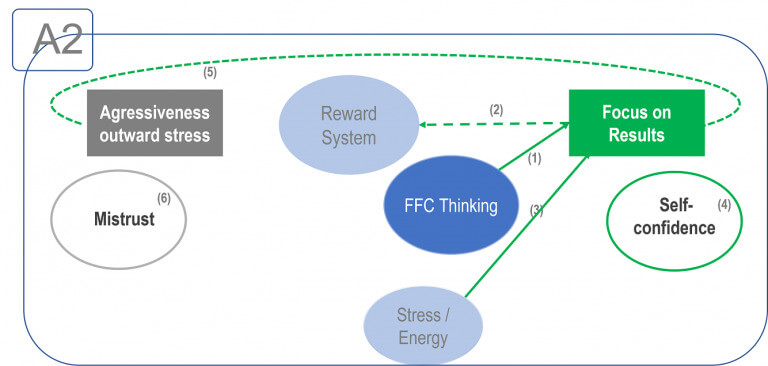

4.2. Dimension A2. Focus on results. Threat System – Fight.

Let’s move on to another PFC approach option in our NeuroQuotient® model of behavioral neuroscience. It is illustrated with Figure 5.

We can also focus on achieving real, tangible, results (1) on medium or long term. In this case the reward system -our motivation to act- will also activate (2). But the energy needed to achieve these results will be much more important than motivation.

It is important to note here that in our behavioral neuroscience model we break down the behavior approach system (BAS) into two parts. Motivation and Action. By the way, the A of the dimensions A1 and A2, refers to these approach behaviors.

This second dimension of the NeuroQuotient® model of behavioral neuroscience may also have a gray, limiting face.

And, when, the focus on results is excessive (5), we might want to achieve results no matter what, showing aggressiveness towards others, expelling stress. Results derived from such actions will make others mistrust us (6), and be perceived as aggressive, arrogant, and selfish individuals.

It is important to remember that animals fight, but humans too often act aggressively

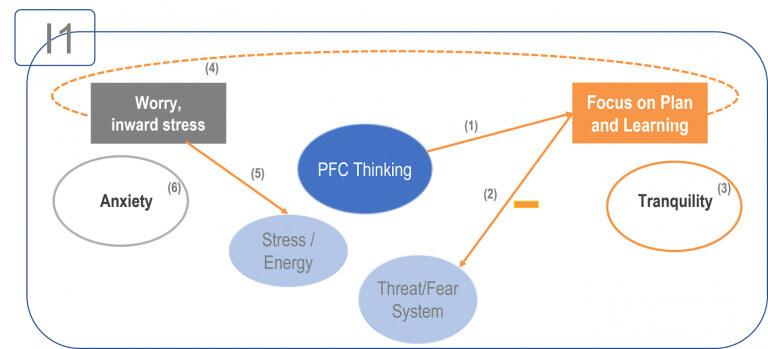

4.3. Dimension I1. Focus on foresight and learning. Threat system -Flight.

Another approach option, surely the main function of the prefrontal cortex, can be summarized in planning and learning (1). Figure 6.

What we consciously or unconsciously want to achieve with this is to generate resources to face the uncertainty of the future and calm down the Threat or Fear System (2). So, we can send ‘neuronal messages’ to this limbic system saying: ‘I know what’s going to happen and I know what to do.’

In this way, we avoid the activation of the amygdala and the emotional result that we achieve is tranquility (3). By appeasing the Threat System, we feel calm and peace.

It is relevant to say that, in this case, we feel safe within our comfort zone. In the former dimension, with self-confidence we feel confident in ourselves, and we are better able to get out of the comfort zone.

But, what happens if our focus on anticipating and planning is excessive? Then we are worrying (4) too much and we are activating the Threat System and Stress (5). Quite the opposite of what we intended.

When animals perceive a threat, they flee. We, humans, can imagine these threats, even if they are not likely to appear. We imagine lions where there may never be.

We can activate the fear system and consequently the stress system simply with our thoughts. But as we don’t flee the stress mount up inside ourselves. The emotional result is that we finally feel anxiety (6).

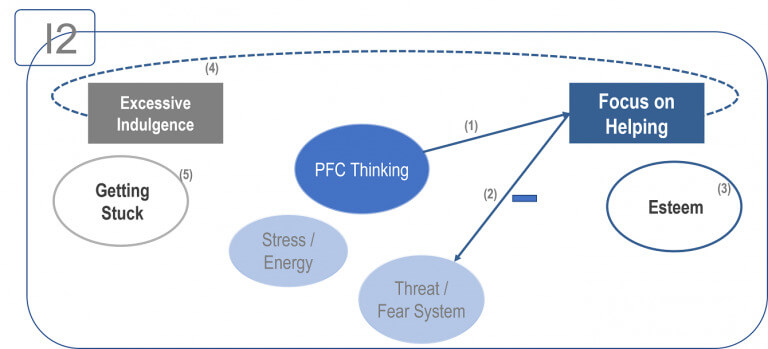

4.4. Focus on helping others. Threat System – Freezing.

We still have one last option in this model of behavioral neuroscience: to focus on helping the others (1). Figura 7.

What we are seeking by doing this is to calm down the Threat System (2), again. This time, teaming up, to face the uncertainties of future together with others, not alone.

And, by helping the others, we also achieve (consciously or unconsciously) their recognition and appreciation. We feel their esteem (3).

But, when the focus on helping others is excessive (4)? What happens when the indulgence towards others is very great, and we depend too much on their recognition? Then we may forget our true needs and stop acting to seek their satisfaction.

Consequently, being very aware of the esteem of others, we can lose self-esteem and we may be left without motivation or energy, and the animal neuro-behaviors of freezing are activated.

The emotional result is that we Get stuck (5). Total inhibition. For this reason, we name the second pair of dimensions of the NeuroQuotient® model I1 and I2, because they are on the side of the limitations related to the BIS (Behavior Inhibition System). On the side of efficiencies, they are neuro behaviors of -containment.

5. The neuro tool.

So far, we have exhaustively looked at the structure of the NeuroQuotient® model of behavioral neuroscience. In the next post, as we pointed out at the beginning, we will focus on the history of its creation and on the neuro tool. With the NeuroQuotient® tool we become aware of how neuro behaviors influence our satisfaction, we focus the process of developing self-leadership and we measure the progress made with the process.